A recent Bark Frameworks job that involved framing three Degas pastels. This is Part I of a two-part article. Part II will appear in the October 2014 Newsletter.

Edgar Degas was an inventive designer of frames. In several of his notebooks from 1879-1884 appear some forty frame profile drawings of striking originality. But only a few of the artist’s frame designs appear to have migrated from the notebooks to the frame shop. And since dealers and collectors were inclined to remove Degas’s own frames and replace them with conventional ornate, gilded mouldings, contemporary examples of Degas’s frame designs are rare. Designing frames for his works is therefore seldom a simple matter of looking at the precedents, since only a handful exist.

We were recently invited to design and make frames for three Degas pastels. Our designer Paul Jordan, consulting with Jed Bark, followed a design process that we have established for framing the works of artists from the Impressionist period until the present. First, we look to the artist’s own preferences; then, to those of his contemporaries and peers. Finally–especially if examples of these are few—we look to those of dealers and collectors at the time. This is just the research agenda—bearing the precedents in mind, we look at the work itself and consider how best to present it in its own terms and for the collection for which it is intended. In framing these three Degas pastels, for each work we took a somewhat different variant of this approach. In this month’s newsletter we will briefly consider a few of Degas’s frames that we have studied and describe our framing solution for one of these pastels. Next month we will discuss the framing of the other two (see also “‘Pictures properly framed:’ Degas and innovation in Impressionist frames” by Elizabeth Easton and Jared Bark. The Burlington Magazine. September 2008).

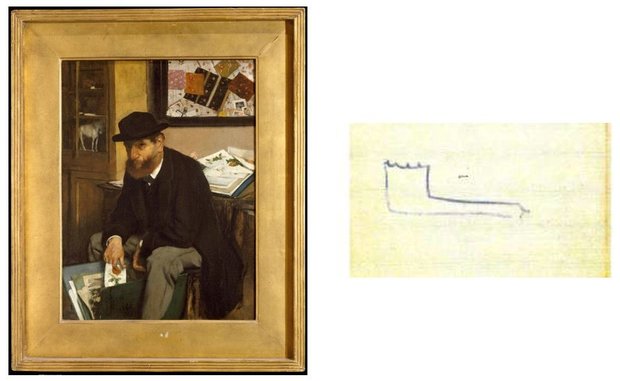

One of the three original Degas frames hanging in The Metropolitan Museum of Art surrounds “The Collector of Prints.” This pastel entered the museum’s collection in 1929 as part of the Havemeyer bequest. Louisine Havemeyer bought it right from Degas’s studio, and he sent it to her in this frame. That this original Degas frame was once in the collection of Louisine Havemeyer is fitting, because she was rare in honoring Degas’s intention that his work be framed simply and in the manner he prescribed. The frame around “Collector” is very simple; a fluted rail and a panel. It is sometimes referred to as a “passepartout” frame, referring to the French designation for what we call in English a “window mat.”

Edgar Degas, “Collector of Prints”, 1866, alongside a passepartout frame sketch by Edgar Degas, from one of his notebooks.

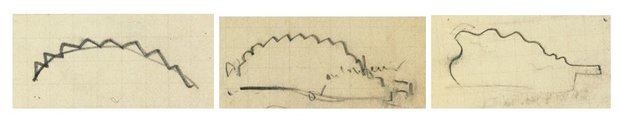

Another devoted collector of Degas’s work who took the artist’s framing preferences into account was Isaac de Camondo. M. Camondo bequeathed his collection of more than 30 works by Degas to the Louvre, and they are now housed in the Musée d’Orsay. The standard Camondo frame echoes the passepartout frame in its structure, but with the addition of a ribbon and stave ornamental border at the face of the outer rail in place of the flutes (image at right). This decorative detail was almost certainly requested by the collector, perhaps so the frames would serve as a bridge between the modern pictures of Degas and Camondo’s collection of eighteenth century furniture.

Illus. Camondo frame w. white liner.

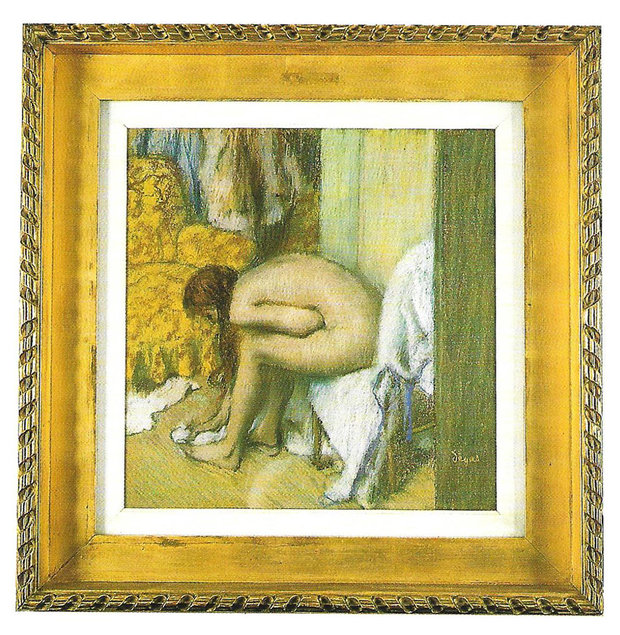

There is another, very different sort of frame designed by Degas of which one example is known to exist, on the pastel portrait of his friends Ludovic Halévy and Albert Boulanger-Cavé. This frame is a convex form, a segment of a column, with a finely fluted surface and no ornamental details whatsoever.

Edgar Degas, “Ludovic Halévy and Albert Boulanger-Cavé in the Wings of the Opera,” 1879. Musée d’Orsay.

Corner detail of the “Halévy – Boulanger-Cavé” frame. This fluted cushion framed, clearly derived from Degas’ sketches, was made more traditional by the framer–fluted frames were no novelty at the time.

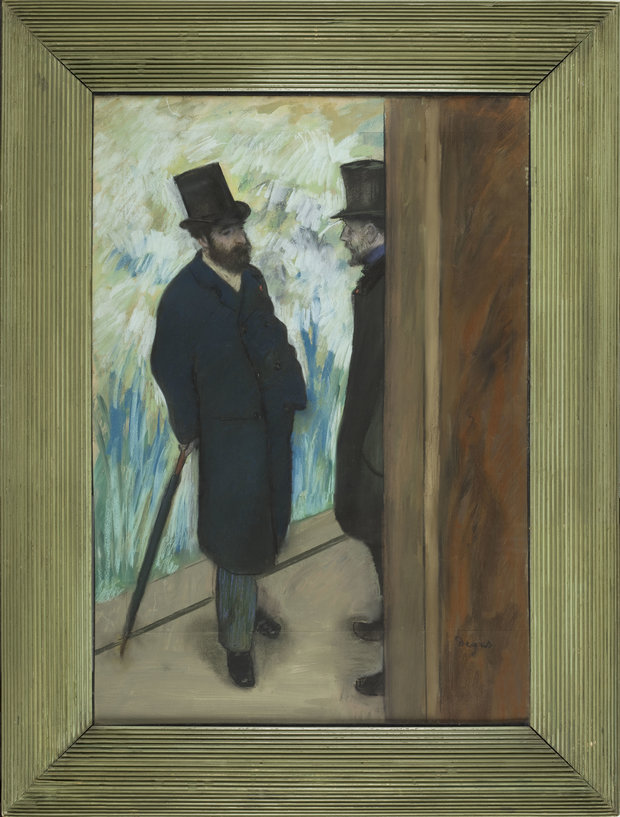

In Degas’s sketchbooks there are three drawings that are related to this frame.

Three Degas sketches of frame profiles (1878-79).

None of these three profiles indicates flutes. The first drawing is serrated, the surface of the second appears to be reeded, and the third, which is not quite a cushion, evokes a series of waves. While Whistler had used a reeded frame of similar design, no examples of the other two designs had ever been made.

For the first of the Degas pastels we were to frame, “Untitled (Dancer Tying Laces),” the three drawings were our source. We have made frames based on these profiles before, most notably for an exhibition of Degas photographs that were exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum in 1998, and for individual pictures by the artist in museum and private collections around the country.

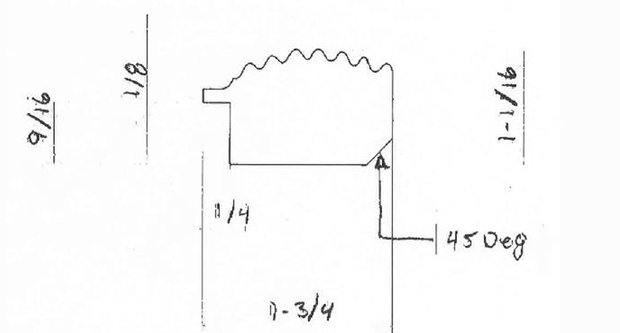

This is the profile we designed for Degas’s photographs in 1998. We named it “Orsay” and continue to use it today.

The pastel, “Untitled (Dancer Tying Laces),” in its old mat, with our Orsay frame corner at lower right.

For this work, we made a slightly wider and deeper frame than Orsay, and as we did in designing the frames for Degas’s photographs, we used the cushion form, with a wavy rather than a reeded or a serrated surface. The ripples reflect light in a lively way, especially with the high burnish of a gold frame. We used 12 karat white gold leaf on black bole and gilded the face and sides. We made an unusually deep 16-ply ragboard mat to replace the thinner mat with a gold bevel. The work was glazed with Optium Museum Acrylic.

In next month’s Newsletter: Degas’s “Two Dancers” in a frame we derived from another of the artist’s sketches — this one, to our knowledge, never used in his lifetime; and “Danseuse Buste,” in a frame that we adapted from an original Caillebotte frame, that has much in common with Degas’s frame designs.

Edgar Degas, “Untitled (Dancer Tying Laces)” in a frame designed and made by Bark Frameworks.

Bark Newsletter, No. 5 – September 2014.