Seventeenth-century Dutch frame design is a subject we return to again and again. Framing art from this period offers our designers the opportunity to utilize our research into historic frames and presents some complex issues in the arena of art preservation.

Rachel Danzing, a paper conservator in private practice who was previously Paper Conservator at the Brooklyn Museum — and with experience at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery — recently approached with such an artwork, on behalf of a collector.

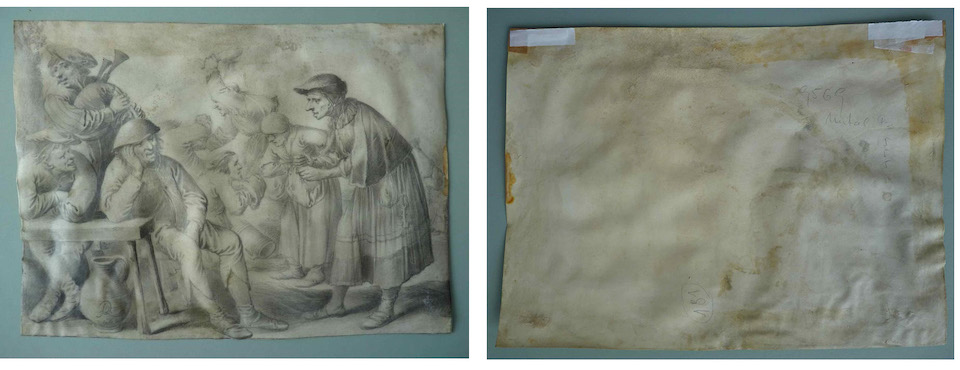

Pieter Quast, Wifely Admonishment, (1644, ink and graphite on parchment) before treatment, recto (left) and verso (right): notice the undulations in the parchment from adhesives and attachments on the verso, and from the natural movement of the material in reaction to changes in ambient moisture.

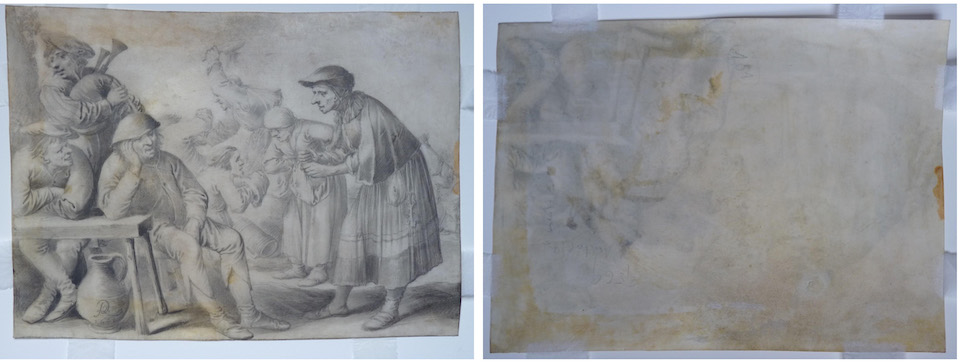

“Wifely Admonishment” by the Dutch painter Pieter Quast (1606 – 1647), an ink and graphite drawing on parchment, needed treatment when it was brought to her by the collector. Several layers of paper attachments were adhered to the verso from previous mountings. Various types of adhesive residues were present on the recto and verso of the drawing. As a result, the drawing was stained, creased and buckled throughout. Rachel removed most of the paper and adhesive residues, reduced the stains, and was able to flatten the parchment so it could be properly viewed and prepared for framing.

Wifely Admonishment after treatment recto (left) and verso (right).

Parchment was a popular medium for artists and writers in Europe until around the 14th century, but by the 1600s, paper was widely available. That Quast chose parchment as his medium in 1644 was clearly a personal preference, and he used it frequently to make drawings depicting groups of peasants.

The print on a showroom table at Bark Frameworks in Long Island City.

Designer Paul Jordan, in consultation with Ms. Danzing, took the media and its support into consideration in making a selection of interior components and a frame construction. Parchment, after scraping and liming, is dried under tension. Unlike leather, it is not tanned, so it is very reactive to changes in relative humidity. In essence, the parchment wants to revert back to its original form, i.e. the shape of the animal’s body from which it came.

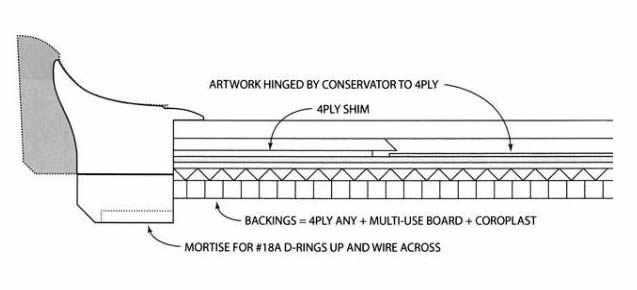

While the planar deformations in the parchment were reduced and evened out with treatment, Jordan placed 4-ply cotton rag board shims between the two layers of the window mat, allowing the parchment space in which to expand and contract with humidity changes without risk of being constricted (details shown in frame cross section below).

To design a profile for this centuries-old work, Jordan looked to our extensive research on 17th century Dutch frames. The client and Jordan decided on a profile called generically holle lijst — in Dutch, “hollow frame.”

Jordan designed the profile deeper than it would have been in the 17th century, allowing space in the back of the frame for materials to protect the artwork from changes in relative humidity (which can also be seen in the profile drawing). Cotton rag board and a Coroplast polyethylene sheet are installed behind the art. The frame is finished in a stain and wax, and is glazed with non-reflective, ultraviolet-light filtering Luxar glass.

After conservation treatment, our design provides long-term preservation and protection for this work, now at home in its new 17th century Dutch profile Bark frame.

Text: Jennifer M. Clark and Rachel Danzing

Photography: Jennifer M. Clark