Bark Frameworks has collaborated for decades with major museums on framing Impressionist, modern and contemporary works from their collections. Bark Frameworks CEO Susan Fisher recently spoke with Lisa Small, Senior Curator of European Art at the Brooklyn Museum, about the Museum’s new installation of their Impressionist and Modern collection, The Real and the Imagined: Monet to Morisot — many of which were reframed by Bark in the early 2000s — to reflect on seeing the works back on view in all their splendor.

Susan Fisher: You have Monet’s “Doge’s Palace” front and center in the new exhibit. Can you tell us more about placing specific artworks in specific places within the exhibition space? Did the framing/treatment of the artworks and how they interacted play a role?

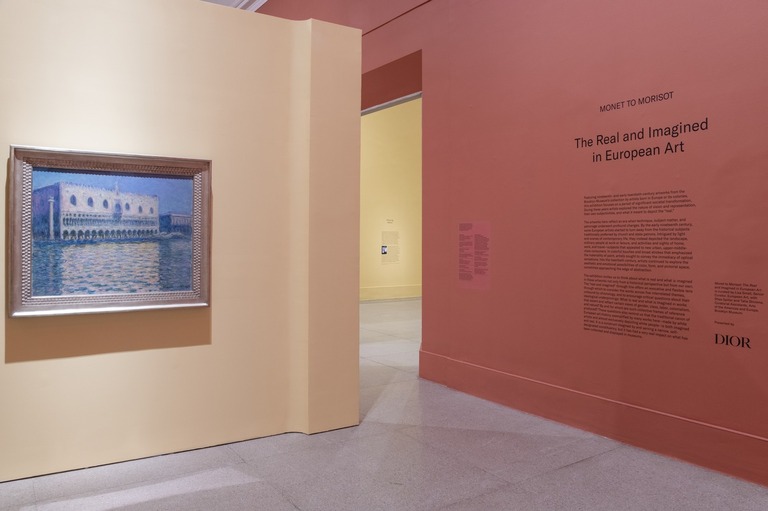

Lisa Small: I was excited to work on this exhibition not only because so many of these great works had not been on view at the museum for a long time, but also because it was going into a new gallery. The museum’s Beaux-Arts court, which was the home of our European paintings for almost 20 years, is a grand and beautiful space but not really a suitable one for so many of our paintings. Now, they are able to be displayed in a more intimately scaled space, which allows for more dialogues among the works and a better overall flow. I organized the presentation thematically so my focus was thinking about the relationship among groups of works and how they might work together and speak to each other within the new gallery design. We have such a range of frames on these works, including some fantastic ones from Bark, but honestly the frames themselves didn’t effect where particular works were installed. But from the very start of my process I knew that Monet’s “Doge’s Palace” would be front and center — not only because of the work itself, which shows Monet’s investment in exploring atmosphere, light, and reflection in his characteristic touch — but because the Bark frame is so perfect! The carved pattern on the frame so subtly echoes the artist’s brushwork!

The entryway to “Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art” at the Brooklyn Museum. At left: Claude Monet’s “The Doge’s Palace,” 1908, in a custom Bark Frameworks frame.

SF: The Bark frames on view in the exhibit required years of research in collections and archives in the US and France by then-Brooklyn Museum European Paintings curator Elizabeth Easton and our founder, Jed Bark. Is that kind of work possible now? What are the challenges facing curators now for this kind of research?

LS: That kind of work is certainly possible, and I’m in awe and extremely grateful for all the work Buffy and Jed did for the collection, but it takes time and money, two things that are in short supply these days at the Brooklyn Museum. So much scholarly and archival information about how artists framed their own work, their theories about the interaction of frame and painting, and how similar contemporaneous work was framed is available, but as each artist and painting is an individual project, it takes the luxury of time and focus to do that research, and I’m the only curator overseeing Brooklyn’s European collection. Not to mention travel, if you want to study the artist’s framed works in other collections. Every day I wish that framing was considered a “sexier” funding opportunity — it would be transformative for us to have people interested in helping us get paintings reframed!

[For more on how Bark Frameworks has worked to help museums reframe their masterworks, see this NY Times article, and this Wall Street Journal article.]

Another view from the exhibition.

SF: Which work in the Impressionist installation would you want to reframe next if you could? In the entire Museum?

LS: Thankfully, Buffy already accomplished so much with our great Impressionist paintings, but we have a beautiful Pierre Bonnard from 1925 that is still in a very inappropriate ornate gold frame — it would really sing in a simple, more minimal frame. Across the entire collection, my number one priority is finding a new frame for our stunning ca. 1520s portrait of a lady as Mary Magdalene by Bartolomeo Veneto. It came to us in 1921 in a really overwhelming and inappropriate frame and I’d love to either find the perfect Renaissance period frame for it, or have a replica period frame custom made for it.

At far left: József Rippl-Rónai, Woman with Three Girls, ca. 1909, in a custom frame by Bark Frameworks.

SF: Do visitors ask you about the frames?

LS: Yes! They often wonder if the artists chose the frames, if they are original, if came to us that way, or if the Museum framed them. It’s always a good opportunity to have the conversation about all the ways paintings get to the museum, what we just have to live with, and what we’ve been able to change and why. And I’m always happy when visitors appreciate some of the most noteworthy frames — all by Bark! — like the extraordinary Rippl-Ronai frame, which evokes the artist’s own designs, or the subtle linear pattern of the Morisot frame, which beautifully contrasts and emphasizes the artist’s delicate brushwork.

“Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art,” is on view at the 5th floor European Galleries of the Brooklyn Museum of Art through May 21, 2023.

Interview Text: Susan Fisher. Photos: Courtesy of Lisa Small; the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

Originally published: July 2022