When I have something framed at Bark, I’m sure it will endure. I’m sure it will be handled correctly and hinged or installed correctly in its frame. It’s a primary attribute of any frame made at Bark that it will keep work safe.

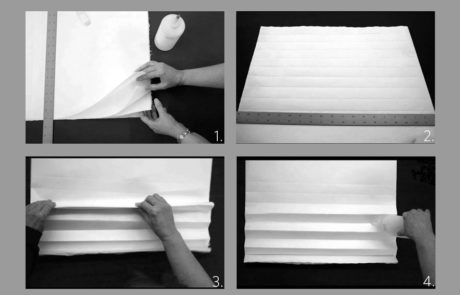

Making Japanese Paper Hinges

If framers understand the properties of art materials, as well as the risks that the environment may pose, then materials and procedures can be chosen that will protect the artwork. Framing practices must also be reversible, so that the adhesives and other materials can be safely removed or reversed by a conservator, even decades from now, with minimal alteration to the work of art.

In a frame designed to meet preservation standards, the materials that surround the artwork constitute a protective envelope. At Bark Frameworks, our fundamental standards are these:

- The matting materials should be 100% cotton fiber, and in most cases, somewhat alkaline to buffer the artwork from atmospheric acidity.

- The glazing (glass or acrylic) must protect art materials that are susceptible to UV damage.

- The interior structure should isolate the artwork from contact with the glazing.

- The framing envelope should allow for movement of hygroscopic materials, such as paper, with changes in humidity; the envelope should be sturdy enough to protect the artwork from external impact.

- Materials in the frame that could damage the work of art, such as acids in wood, must be isolated.

Explore Methods and Materials

If framed with acrylic glazing, its static charge may pull the sheet of Japanese paper forward and into contact with the glazing, putting the artwork at risk. So non-static glazing must be used or the frame must be designed to prevent this.

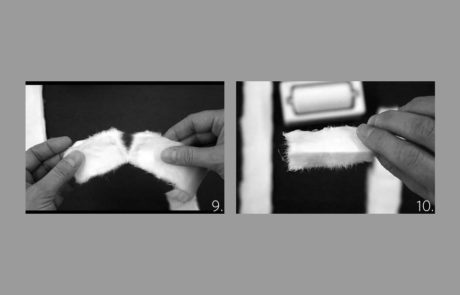

Most of the objects we frame are works on paper. In framing works on paper we take into account the many differences in the nature of various papers. For example, Japanese papers are often light; some are like gossamer, with a modest sizing of vegetable gelatin to reduce water absorption, so they are very pliant.

If framed with acrylic glazing, its static charge may pull the sheet of Japanese paper forward and into contact with the glazing, putting the artwork at risk. So non-static glazing must be used or the frame must be designed to prevent this.

Most modern and contemporary works on paper utilize machine-made paper which has a decided grain direction. The sheets expand and contract with changes in humidity far more across the grain than parallel to the grain.

Of course, artworks may be made with plastics and other materials whose properties differ from paper in their reactions to light and to changes in temperature and humidity. Their properties must be taken into account in framing them.

Glazing samples on matboard show the tints of different glazing materials

We do our own research on many aspects of the framing process, including framing materials like glazing. Just last year we wrote an article on the properties of acrylic glazing; a few years prior to that, we wrote about the long-term stability of UV-blocking acrylic.

In 1991, Jared Bark wrote a paper, Glazing for Framing and Case Making, in which he listed the properties of the ideal glazing material. What he outlined in that paper about the properties of ideal glazing material remain relevant today. In the years since, improvements have been made in frame glazing, and there are now many choices of glazing with a wide set of characteristics.

Outlined below are the properties of the ideal glazing material, with added information about products on the market that meet these criteria. We also indicate the different aspects of these materials and the circumstances for which they are recommended.:

Transmits all the light in the visible spectrum and is therefore un-tinted

- Acrylic glazing (Acrylite and Plexiglas are two well-known brands) is virtually un-tinted, though in its UV blocking version has a slight green, blue or gray cast.

- Glass may appear slightly green due to iron oxide impurities in the glass. “Water white” or “low iron” glass transmits virtually the whole spectrum and has almost no tint, but also allows transmission of more UV than conventional glass.

Blocks ultraviolet light

- Acrylic glazing has been available with UV blocking agents for decades.

- Coated and laminated glass sheets are available that block UV as effectively as UV blocking acrylic.

Is non-reflective

- Several varieties of coated “anti-reflective” glass are available from framers. All eliminate about 99% of reflection. Windows and lights are reflected though, and the reflection is tinted.

- There is one coated acrylic, Optium, which is similar to the coated glass materials.

Carries no static charge

- Glass carries almost no electrostatic charge.

- Acrylic sheet is subject to high static charge, especially when humidity is low. Anti-static acrylic cleaning solutions will reduce the charge temporarily. Loose media, such as charcoal, chalk or pastel, and thin or lightly sized papers (such as Japanese papers) will be attracted to static charged acrylic glazing.

- Optium acrylic’s coating, applied to reduce reflection, also virtually eliminates static charge.

Does not expand and contract in response to temperature and humidity

- Glass does not expand or contract in response to changes in humidity, and very little to changes in temperature—even less than aluminum or steel.

- Acrylic expands and contracts about ten times as much as glass in response to temperature change; and it responds to changes in humidity, though to a lesser degree and more slowly than it responds to temperature change.

Is close to unbreakable—and if broken, does not produce sharp splinters

- Glass shatters. If a frame glazed with glass must be shipped, the glass should be masked with an adhesive film (such as Glass Skin). Glasses coated to reduce reflection are sometimes damaged by such adhesives, so manufacturer’s guidelines should be followed. Laminated glass, if broken, adheres to its inner plastic layer, limiting or eliminating loose shards of sharp glass in the frame.

- The impact resistance of acrylic glazing is several times that of picture glass; this property is hardly affected by changes in temperature. It rarely cracks or breaks in shipping, and if it does, the broken edges are not as sharp as glass. For these reasons, and because tape removal is very difficult, it should not be taped. If needed, impact resistant acrylic is also available.

- Polycarbonate is more resistant than acrylic, but its other properties make it less attractive than acrylic for framing.

Is abrasion-resistant

- Glass is abrasion resistant.

- Coated glass must be treated carefully. The surface can be scratched and once scratched is irreparable.

- Acrylic can be manufactured with an abrasion resistant surface. This surface is less tough, however, than the surface of glass.

Is light weight

- Glass is about twice as heavy as acrylic, and this can become a major issue for large frames. For example, a 48” x 96” sheet of 4.5 mm (about 3/16”) acrylic weighs about 35 pounds and a sheet of glass that size weighs about 70 pounds. But for large frames, thicker laminated glass is generally chosen and a sheet this size would require a thickness of 6 mm and would weigh about 100 pounds.

Is rigid and free of distortion

- Glass is rigid and free of distortion

- Acrylic sheet is flexible, and subject to deflection which distorts reflections. A concern for framers is that glazing may bow in, touching a framed work of art. This may be caused by the expansion of acrylic that is too tight in the frame, exhibition lights that warm the interior of the frame, or differences in relative humidity inside and outside the frame, with the acrylic bowing to the more humid side. The thinner the sheet, the more likely the bowing. Acrylic glazed frames should not be shipped lying flat since horizontal bowing is substantial and the glazing could contact the surface of the framed artwork.

Is available in large size

- Maximum for laminated glass is about 6’ x 10’.

- Maximum for acrylic sheet is about 9’ x 14’.

- Maximum for Optium acrylic sheet is 6’ x 10’.

Shows no effects of aging

- Glass is ageless as far as framing is concerned.

- Acrylic is an organic material and all organic materials age. But the process is glacially slow, and imperceptible. It is often assumed that acrylic yellows with age. If it does, the human eye can’t perceive it.

- Whether UV blocking acrylic loses its effectiveness over time has been an unanswered question until recently.

In early 2011 we tested ten sheets of UF3 (UV blocking) acrylic that we had installed in frames during the 1980’s. We found that they were still excellent UV blockers. All these roughly 25 year old sheets of acrylic blocked over 99% of UV. See full article.

In choosing which glazing sheet to use, some of the questions to consider are:

- Is the work susceptible to UV damage?

- Under what conditions—such as lighting, climate control, public access—is the work likely to be displayed?

- Is it intended that the work will be shipped?

- Is the media loose (charcoal, pastel or similar)?

The answers to these questions will inform decisions about glazing choice. Another major consideration is cost. Costs for the more than twenty-five glazing materials we now use vary widely, with the most expensive costing about fifty times more than the least expensive.

Burnishing the inside edge of a mat.

The window mat and back mat should be made from cotton fiber (commonly called 100% rag or museum board).

Chemically purified wood fiber (sometimes called conservation board) is considered by some conservators to be an acceptable alternative. Cotton fibers are almost pure cellulose however, and to remove lignins and other impurities from wood pulp is a complicated process. At Bark Frameworks we prefer to use the material which requires the least purification, since industrial processes are not always reliable.

The matboard should be entirely free from lignins or groundwood and should be sized with a neutral or alkaline size. The pH of the board should be from 7 to about 9, and it should contain a calcium carbonate alkaline reserve, or buffer, of up to 3%.

Boards made specifically for framing certain photographs do not contain an alkaline reserve and have a neutral pH. Dye transfer prints and Cyanotypes should be framed in these unbuffered mats. Chromogenic color prints and albumen prints should also be kept away from alkaline materialss, according to many conservators. RC and fiber-base black-and-white prints should be safe in alkaline mats (though some conservators may disagree). Cibachromes can be safely framed with either buffered or unbuffered materials. In general mat boards that have passed the Photographic Activity Test are the safest to use in framing photographs.

Mat boards of conservation quality are made in a range of colors. These are made with non-acidic direct dyestuffs or pigments, unlike conventional dyes which require acidic mordants to set the dyes. Nevertheless, conservators often feel that these colored boards should be used with caution, since the pigments may scuff off and there is a risk of dyes bleeding under certain conditions, such as very high humidity. And colored mat boards should not be in direct contact with photographs.

Special mat boards are made that incorporate zeolite materials to adsorb volatile organic compounds and other indoor pollutants. Matting can also include silica impregnated sheets to help control relative humidity.

Window Mats

The window mat has an esthetic role, in providing a field around the work of art, which isolates it from both the frame and its surroundings.

The major protective function of a window mat is to separate the work of art from the glazing surface. The mat also helps support the perimeter of the paper sheet. Window mats are made commercially as thin as 2-ply, about 1/32″ thick, and up to 8-ply which is 1/8” thick. At Bark Frameworks we custom mount thicker mats, up to about 3/8” thick. Thick window mats are sometimes preferable on esthetic grounds, and often are safer for the framed work.

There is no rule that above a certain size a window mat of a given depth should be used. In this as in so many other matters, it’s a question of judgment, in which such issues as display conditions and media must be weighed.

Cutting fillets.

Fillets

Sometimes a window mat is not deep enough to protect a wavy or large work on paper. In such cases, and when for esthetic reasons a window mat is inappropriate, a spacer (known as a fillet) between the glazing and the back mat may be used.

We use fillets from 1/8″ deep up to about 3″ deep. Fillets may be made from mat board, acrylic or other stable plastic, or wood, which should be sealed.

Fabric Covered Mats

Silks and linens are often mounted on matboard for use as both window mats and back mats. When we tested a number of silks and linens for pH we found them all to be acidic. Whether or not a particular piece of cloth tests in the acid range, silk and linen should not be viewed as archival materials. If they must be used in a frame they should be isolated from the artwork by mat board of at least 2-ply thickness. For a window mat this means lining the underside. When we are required to float an artwork on a silk or linen-covered back mat we cut a sheet of matboard slightly smaller than the work of art and fix it between the work and the back mat. None of these solutions is as safe as simply using rag mat board.

Back Mats

Our guillotine shear cuts large sheets of matboard.

The back mat is the support to which works of art are hinged. It is usually attached along one of its long sides with a long tape hinge or “spine” to the window mat.

Back mats should be of 4-ply mat board, unless the frame is over-sized. For frames over 40″ or so in both directions, it may be necessary to make a more rigid backing. One option is to use 8-ply mat board. A solution we developed and sometimes choose at Bark Frameworks is to make a “laminated back mat”; we mount mat board to both sides of a core material, such as archival Coroplast or acrylic sheet. For very large works a panel can be constructed with aluminum clad material. Bark Frameworks stocks rag paper manufactured for us to our specifications for seamless surfaces of such panels. Our paper is 79” wide, and can be ordered directly from our shop, by calling (718) 752-1919 or contacting our shop directly.

Backing Board

The backing board is installed behind the back mat. Its main role is to provide another layer of protection to the back of the work of art. It is the surface to which labels are usually applied. Backing boards can be made from either acid-free corrugated board or archival quality polypropylene (such as Coroplast) or archival polycarbonate.

The best paste for hinging is made from either wheat starch or rice starch. Most paper conservators use wheat starch; after testing half a dozen paste recipes, at Bark Frameworks we continue to choose rice starch, as we have for decades. We use it because we found that it was smoother than wheat starch paste. We do not add a preservative partly out of concern for our own health but also because some preservatives have been shown to turn brown with time. We make our paste at the beginning of the week, and it is refrigerated; we take out as much as we will need each morning.

The best paste for hinging is made from either wheat starch or rice starch. Most paper conservators use wheat starch; after testing half a dozen paste recipes, at Bark Frameworks we continue to choose rice starch, as we have for decades. We use it because we found that it was smoother than wheat starch paste. We do not add a preservative partly out of concern for our own health but also because some preservatives have been shown to turn brown with time. We make our paste at the beginning of the week, and it is refrigerated; we take out as much as we will need each morning.

Corner Pockets

Corner pockets are sometimes a good alternative to hinges. They are used most often with photographs but can be used with any work on paper provided that it will be overmatted and that it is small enough and rigid enough that it will not slip out of the corner pockets. At Bark Frameworks we designed and usually make two layered corner pockets, with a Japanese paper inner-pocket extending beyond an over-pocket made of Mylar (archival polyester). We arrived at this method after finding that Japanese paper pockets sometimes tore, especially when framed works are shipped. Mylar is very strong and an excellent material for pockets, but the edges of Mylar are so hard and sharp that we felt they endangered the surface of the artwork held in the pocket. The Japanese paper inner pocket protects the surface of the artwork, and the Mylar outer pocket provides strength. Corner pockets should be attached to the back mat with a bit of room at the sides and top for the artwork to expand.

Regarding Pressure Sensitive Adhesives

All pressure sensitive tapes and adhesives, even those advertised as “archival” should be avoided. The Library of Congress states on its Preservation web site: “In most instances, the object can be hinged with long-fibered Japanese tissue adhered with wheat or rice starch paste. There is no known pressure-sensitive adhesive suitable for hinging an object.” The American Institute for Conservation brochure “Framing Works of Art on Paper” makes a similar statement: “Avoid methods of attaching works of art to back mats such as dry- mounting, lamination, spray mount, rubber cement, or pressure-sensitive tapes (e.g, masking, office, or even those referred to as “archival” or “preservation” tapes). The adhesives in these materials can seep into paper, become discolored, brittle, and difficult to remove.”

All pressure sensitive tapes and adhesives, even those advertised as “archival” should be avoided. The Library of Congress states on its Preservation web site: “In most instances, the object can be hinged with long-fibered Japanese tissue adhered with wheat or rice starch paste. There is no known pressure-sensitive adhesive suitable for hinging an object.” The American Institute for Conservation brochure “Framing Works of Art on Paper” makes a similar statement: “Avoid methods of attaching works of art to back mats such as dry- mounting, lamination, spray mount, rubber cement, or pressure-sensitive tapes (e.g, masking, office, or even those referred to as “archival” or “preservation” tapes). The adhesives in these materials can seep into paper, become discolored, brittle, and difficult to remove.”

There are exceptional cases, such as when the support is made of plastic, in which a pressure sensitive or heat sensitive adhesive must be used. Whenever an unusual adhesive is used, we affix a dated explanatory label to the backing board to help the conservator who must remove it at a later date.

Read More about pressure sensitive adhesives in this article with Margaret Holbein Ellis.

Wiring frames with strainers.

We often install a strainer in the back of the frame for strength and stability. A strainer is similar to a stretcher, with one difference—a strainer’s corners are not adjustable. One advantage of backing a frame with a strainer is that it can be easily removed and re-fitted without the use of framer’s tools.

There are various ways of hanging frames: Screw-eyes and wire; D-rings with or without wire; picture rail hanging systems; and wooden cleats or aluminum zee clips, which are often the best for heavy works. For museum clients we have designed a special Tee Plate with a number of improvements over conventional hardware for screwing frames to the wall. Many museums prefer this hardware for secure installation. You can order these Tee Plates directly from our shop (in packs of 100), by calling (718) 752-1919 or contacting our shop directly.

The frame should not hang flush against the wall. Bumpers can be mounted on the back of the frame or strainer to allow air circulation between the frame and the wall, which will discourage mold growth.

At Bark frameworks, for large and heavy works we install proprietary nylon web carrying straps so framed works can be moved with safety for the work, the frame and the art handler. These too are available from our online store.

Sealing Frames

The question of sealing frames is not clear-cut. Since one of our primary goals is to protect framed artwork from environmental threats such as atmospheric pollutants and abrupt changes in humidity, it stands to reason that a sealed frame would make a fine solution. But whenever we seal something out, we also seal something in.

To the degree that it is possible to seal a frame envelope, with Mylar backing and careful taping for instance, we will also be sealing in moisture, which may damage the work, as well as solvents off-gassing from the artwork itself.

Partial sealing techniques can eliminate some risks. One method, when the artwork has been overmatted, is to apply an appropriate tape around the perimeter of the envelope, overlapping the front of the glazing by about 1/8″ and continuing around to the back edge of the back mat. In general, waterproof backing boards are preferred.

Sometimes it is prudent to seal the inner surface of a wooden frame. For this purpose, we may use a strip of rag board or Mylar. An even better vapor and gas barrier is MarvelSeal, an aluminized nylon and polyethylene barrier film.