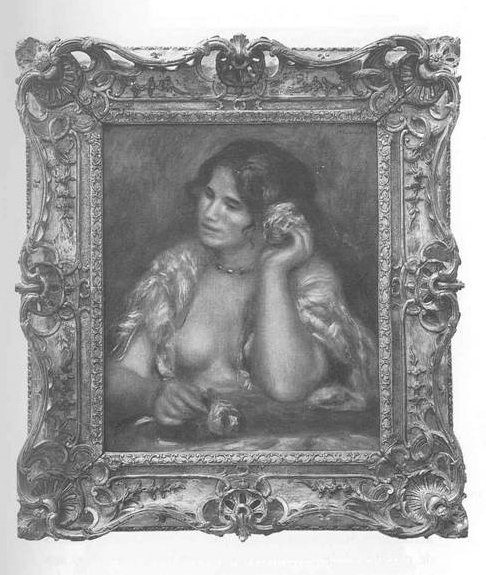

The exhibition “The Renoir Returns” opened at the Baltimore Museum of Art several weeks ago. The centerpiece of the exhibition, the artist’s “On the Shore of the Seine” (c. 1879), is a small landscape that was stolen from the museum more than 60 years ago. The painting was restored to the BMA by a federal judge after a woman, who claimed to have bought it at a flea market because she liked the frame, tried to sell it at auction. Learn more about the fascinating story of the painting’s recovery.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, “On the Shore of the Seine,” c. 1879. NPR.com.

Impressionist pictures were often framed by dealers and collectors in ornate frames like this one, even though many of the Impressionists–especially Degas, Pissarro, Cassatt and Morisot–rejected them. A Rococo frame such as the one above, on a Degas, would have seriously annoyed the artist.

But, we would be wrong in assuming that such a frame would have met with Renoir’s disfavor. Alone among the Impressionists, Renoir valued old, carved frames–he appreciated them for their craftsmanship. The son of a tailor, and a porcelain painter himself as a boy, Renoir’s background as a member of the artisan class was unique among the Impressionists. It is therefore understandable that he had no interest in the austere framing experiments of his colleagues in the late 1870’s. He was, after all, a trained artisan, and these frames made no particular use of the craft, skill, and experience of an artisan.

Furthermore, Renoir admired 18th c. French painting, and his use of 18th c. frames may have served, for him, as a bridge between his work and the work of 18th c. masters.

Pierre-August Renoir, “Gabrielle a la Rose” (1911), image from Isabelle Cahn.

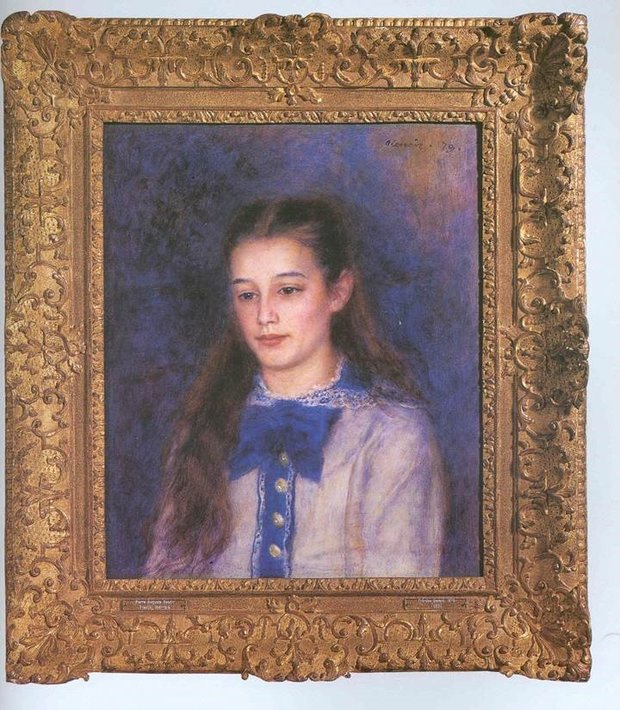

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, “Portrait of Thérèse Bérard”, 1879, with a French Louis XIV corner-and-centre frame. Williamstown, Massachusetts, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.

Jean Renoir wrote that his father “would tolerate only old frames carved in hard wood, ‘which showed the hand of the craftsman.’ Renoir’s taste in frames, as indeed in everything, surprised people who prided themselves on having ‘good taste.’ The expression annoyed him, and by way of defiance he would proclaim that he had ‘bad taste.’ Bright colors are accepted nowadays in women’s clothes…but in his day it was only country people who wore them–genteel people dressed in sober colors. The same attitude applied to picture frames and antique furniture -they were admired for their quality, but their color and the golds, especially, had to be faded. My father pointed out that the frames had been new originally, and that they were therefore meant to shine ‘like gold.’ Several times he treated himself to having a favorite frame re-gilded with gold leaf; for instance, the frame for the portrait he did of me as a hunter. Re-gilded 50 years ago, it still shocks people of ‘good taste.’ It is an Italian frame of the late 17th century. Renoir chose it himself in an antique shop in Nice. He felt that a massive frame was necessary to set off the picture properly, ‘especially in a drawing room in the Midi, where there is so much else to tempt the eye.'”

To a viewer who knew that Impressionists were well-known for simple, painted frames, the 18th c. frame on the Renoir at the Baltimore Museum of Art might look like a gaudy anachronism. But the artist himself almost certainly would have approved.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, “Jean as a Huntsman” (1910). Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Donated to the Museum by Jean Renoir, in its original frame.

By Jed Bark, Bark Frameworks.

Bark Frameworks Newsletter, No. 5 – September 2014.