Framing for “Danseuse Buste, 1897”

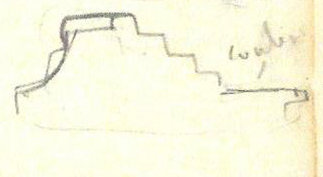

To frame the Degas pastel we discussed in our last Newsletter, we made a profile that was closely related to three drawings from his sketchbooks. As we noted, a few original Degas frames of this genre still can be seen. But there are no surviving examples of frames made from most of his drawings, and it is doubtful if more than a handful were ever made in his lifetime. Over the past fifteen years though we have made frames from about a dozen of the profiles Degas drew. One of them is shown below, a drawing from his sketchbook of 1878-79.

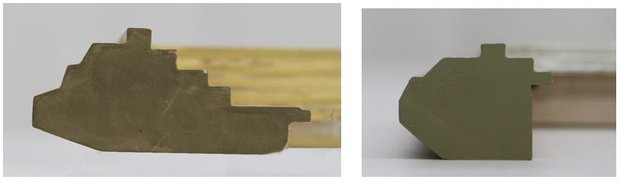

For framing “Danseuse Buste,” a small and fine pastel, the frame as it appears below, in the first sketch, was overpowering, but we thought that with some modification it could effectively border the work. We first considered making it in a smaller scale, but decided that reducing this intricate profile to a dimension that would be suitable for the pastel would make its special details unrecognizable. We chose instead to eliminate some of the inner facets, including the wide flat slip at the sight edge and keep it in this larger scale.

The drawing suggests two variants. We followed what seems to be the original line, so the moulding we made consists of a series of steps. At some point we may make the other version, which shows a sweeping curve at the back of the profile.

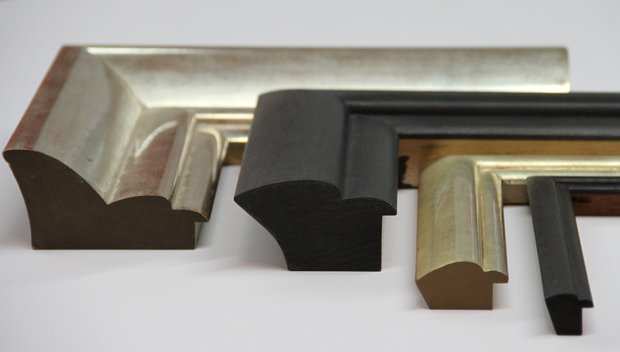

We made the moulding for the pastel from the sections to the left. You can see the line, down the center of the original sketch, where the rabbet of the pastel frame has been drawn.

Our first corner made from the entire drawn profile on the left, and the smaller section we made for “Danseuse Buste.”

We gilded the frame with 9 karat white gold laid over black clay—a cool and restrained finish for this delicate work.

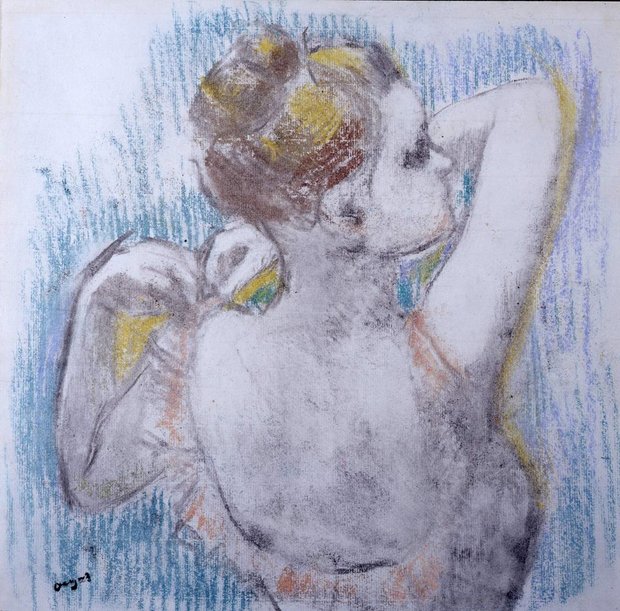

Edgar Degas, “Danseuse Buste, 1897,” unframed.

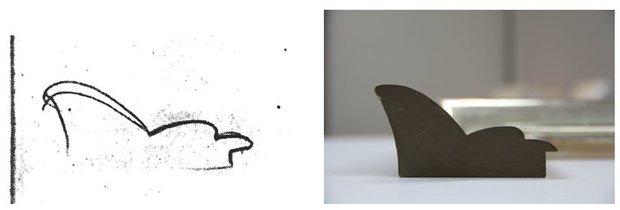

We made this small frame from the original sketch on the left. It hangs in our showroom, with one of our handmade mirrors. The frame’s planes of varying widths, some tilted, create a syncopated rhythmic border.

“Danseuse Buste, 1897,” framed by Bark Frameworks, 2014.

Detail, “Danseuse Buste.”

The pastel is matted with a 12 ply mat, the whole sheet exposed, and glazed with laminated, UV shielding, non-reflective glass. Pastels should always be protected from ultra-violet light.

This approach, to use a section of the profile drawing, is one that we have followed with Degas’s designs before. An example of a Degas corner we made is shown below in section and plan, next to the drawing from Degas’s sketchbook. When Jed Bark looked through Degas’s sketchbooks at the Bibliothèque Nationale in 1999, he was surprised to note that the drawing in Degas’s hand was 4 ½” wide, clearly drawn to be translated directly by the framemaker into a frame. We don’t know if this profile was ever actually fabricated; there are none like it in existence.

We have occasionally used the whole profile as drawn, but more often we have made frames from the inner two sections.

Drawing from Degas’s sketchbook and our moulding made from it.

Our first corner made from Degas’s drawing is seen on the left with three samples in which we used just the inner sections..

Framing for “Two Studies of a Dancer”

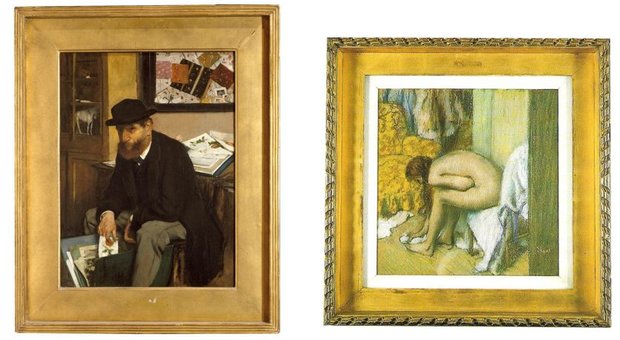

The third Degas pastel that we framed in this project is shown “The Two Studies of a Dancer”. In framing it, we were strongly influenced by his passe-partout frame and by the frame used by the collector Isaac de Camondo for framing his works by Degas; we referred to both of these frames in Part I and they are shown below.

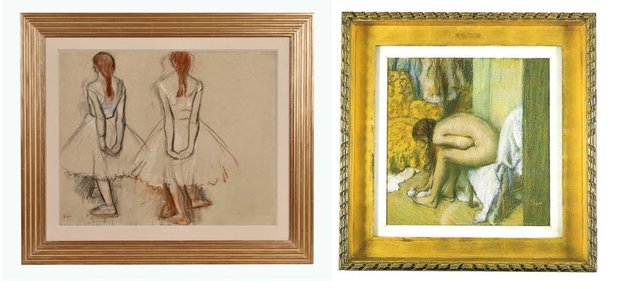

Left: Edgar Degas, “Collector of Prints,” 1866. Right: Degas’s “Nude Wiping Her Left Foot,” in its Camondo frame, 1886-88.

Edgar Degas, “Two Studies of a Dancer,” unframed.

A number of the Impressionists shared Degas’s interest in radical framing. One of them, Gustave Caillebotte, however, was never cited in the press as an innovator in framing. More than a decade younger than Degas, Caillebotte first exhibited his work in the second Impressionist exhibition in 1876.

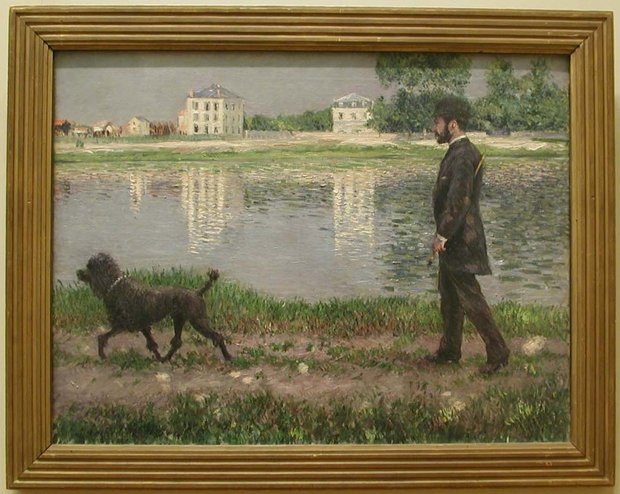

There is only one contemporary mention of Caillebotte frames; in a review of an exhibition of his work, the elegant gold framing was noted. But evidence exists that Caillebotte too was moved by the radical frames of Degas. On his picture of M. Richard Gallo walking his dog, shown below, is its original frame, a simple fluted profile, not gilded but finished with bronze paint.

Gustave Caillebotte, “Richard Gallo and His Dog Dick at Petit Gennevilliers,” 1884. Private collection.

Corner of the frame above. It is simple and modest, but it is not cheaply made. The corner joints are half-lapped miters, a strong and durable joint that required the hand of a skilled woodworker.

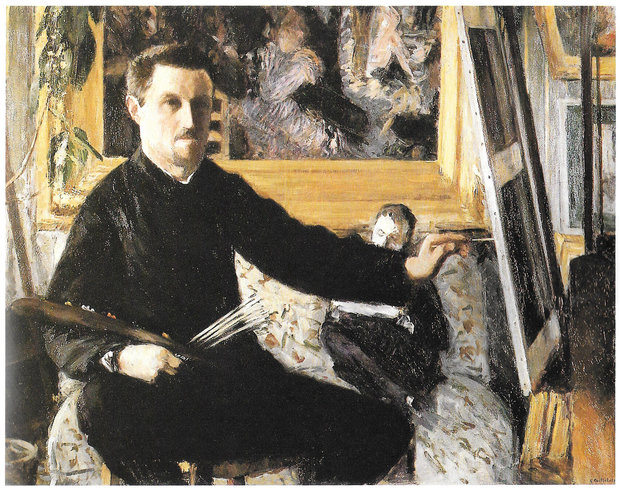

Gustave Caillebotte, “Self Portrait at the Easel” (1879-80). The painting in the background, Renoir’s “Le Moulin de la Galette,” is surrounded by a huge gold frame, a far cry from the restrained and often painted frames characteristic of Degas, Pissarro, and others in the Impressionist group.

We framed a large Caillebotte for the Brooklyn Museum several years ago. The picture depicts the bridge at Argenteuil, with its structural elements evident and a train coming down the track. We found the Gallo frame with its rigorous linearity, to be very effective.

Though much wider, at almost four inches, the Caillebotte frame is very similar in form to the outer rail of Degas’s passe-partout frame. This framing element of parallel bands separated by channels or flutes was to appear in the following years on frames of the neo-Impressionists, in various forms.

After framing the Caillebotte for the Brooklyn Museum, we had the moulding milled at a smaller scale, intending it for framing works on paper. Here below are a few sample corners of that moulding from our showroom.

We chose this Caillebotte profile to frame Degas’s “Two Studies.” We followed, generally, the Camondo frame example, employing a narrow, deep mat much as the white liner is used in the Camondo frame, to provide an unadorned field to separate picture and frame.

“Two Studies of a Dancer” in our frame, and Degas’s “Nude Wiping Her Left Foot” in a Camondo frame at Musée d’Orsay.

Edgar Degas, “Two Studies of a Dancer.” Our frame is gilded in “moon gold” a gold leaf containing some copper, over dark red clay. The mat is 16 ply ragboard, about 1 ½” wide. The UV-blocking, non-reflective glazing is the same in all three frames.

Degas’s frame designs continue to serve as a rich source for presenting works of art from the 19th century until today. The complexity and creativity of his mouldings continue to inspire. We framed a Willem de Kooning, for example, in a frame that was almost identical to Degas’s frame on “The Collector of Prints”, but finished in a way that was similar to the painter Signac’s version of Degas’s passe-partout frame.

Gustave Caillebotte, “Bridge at Argenteuil,” 1885-87. Brooklyn Museum of Art.

Degas passe-partout frame corner at left. Caillebotte corner at right.

By Jed Bark

Bark Newsletter, No. 6 – October 2014.